The Magic Poker Robert Coover Summary

The same fairy tale ‘Hansel and Gretel’ is adopted by Robert Coover with the title ‘The Gingerbread House’. He used the device of exaggeration to parody the form of the original. In order to do so, he eliminated the first part of the story that is exposition of the crisis and the last part such as complication and denouement. Metafiction, however, became particularly prominent in the 1960s, with authors and works such as John Barth's Lost in the Funhouse, Robert Coover's 'The Babysitter' and 'The Magic Poker', Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five, John Fowles' The French Lieutenant's Woman, Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49 and William H. Gass's Willie Master's.

Metafiction is a form of fiction that emphasizes its own constructedness in a way that continually reminds the reader to be aware that they are reading or viewing a fictional work. Metafiction is self-conscious about language, literary form, and storytelling, and works of metafiction directly or indirectly draw attention to their status as artifacts.[1] Metafiction is frequently used as a form of parody or a tool to undermine literary conventions and explore the relationship between literature and reality, life, and art.[2]

Although metafiction is most commonly associated with postmodern literature that developed in the mid-20th Century, its use can be traced back to much earlier works of fiction, such as Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (1387), Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote (1605), Laurence Sterne's The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759), William Makepeace Thackeray's Vanity Fair (1847), as well as more recent works such as Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1979) and Mark Z. Danielewski's House of Leaves. Metafiction, however, became particularly prominent in the 1960s, with authors and works such as John Barth's Lost in the Funhouse, Robert Coover's 'The Babysitter' and 'The Magic Poker', Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five,[3]John Fowles' The French Lieutenant's Woman, Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49 and William H. Gass's Willie Master's Lonesome Wife.

- 2Forms

- 3Examples

History of the term[edit]

The term 'metafiction' was coined in 1970 by William H. Gass in his book Fiction and the Figures of Life.[4] Gass describes the increasing use of metafiction at the time as a result of authors developing a better understanding of the medium. This new understanding of the medium led to a major change in the approach toward fiction. Theoretical issues became more prominent aspects, resulting in an increased self-reflexivity and formal uncertainty.[5][6]Robert Scholes expands upon Gass' theory and identifies four forms of criticism on fiction, which he refers to as formal, behavioural, structural, and philosophical criticism. Metafiction assimilates these perspectives into the fictional process, putting emphasis on one or more of these aspects.[7]

These developments were part of a larger movement (arguably a 'metareferential turn'[8]) which, approximately from the 1960s onwards, was the consequence of an increasing social and cultural self-consciousness, stemming from, as Patricia Waugh puts it, 'a more general cultural interest in the problem of how human beings reflect, construct and mediate their experience in the world.'[9]

Due to this development, an increasing number of novelists rejected the notion of rendering the world through fiction. The new principle became to create through the medium of language a world that does not reflect the real world. Language was considered an 'independent, self-contained system which generates its own 'meanings.'[10] and a means of mediating knowledge of the world. Thus, literary fiction, which constructs worlds through language, became a model for the construction of 'reality' rather than a reflection of it. Reality itself became regarded as a construct instead of an objective truth. Through its formal self-exploration, metafiction thus became the device that explores the question of how human beings construct their experience of the world.

Robert Scholes identifies the time around 1970 as the peak of experimental fiction (which metafiction is an instrumental part of) and names a lack of commercial and critical success as reasons for its subsequent decline.[11] The development toward metafictional writing in postmodernism generated mixed responses. Some critics argued that it signified the decadence of the novel and an exhaustion of the artistic capabilities of the medium, with some going as far as to call it the 'death of the novel'. Others see the self-consciousness of fictional writing as a way to gain deeper understanding of the medium and a path that leads to innovation that resulted in the emergence of new forms of literature, such as the historiographic novel by Linda Hutcheon.

Forms[edit]

According to Werner Wolf, metafiction can be differentiated into four pairs of forms that can be combined with each other.[12]

Explicit/implicit metafiction[edit]

Explicit metafiction is identifiable through its use of clear metafictional elements on the surface of a text. It comments on its own artificiality and is quotable. Explicit metafiction is described as a mode of telling. An example would be a narrator explaining the process of creating the story they are telling.

Rather than commenting on the text, implicit metafiction foregrounds the medium or its status as an artefact through various, for example disruptive, techniques such as metalepsis. It relies more than other forms of metafiction on the reader's ability to recognize these devices in order to evoke a metafictional reading. Implicit metafiction is described as a mode of showing.

Direct/indirect metafiction[edit]

Direct metafiction establishes a reference within the text one is just reading. In contrast to this, indirect metafiction consists in metareferences external to this text, such as reflections on specific other literary works or genres (as in parodies) and general discussions of aesthetic issues; since there is always a relationship between the text in which indirect metafiction occurs and the referenced external texts or issues, indirect metafiction always also impacts the text one is reading, albeit in an indirect way.

Critical/non-critical metafiction[edit]

Critical metafiction aims to find the artificiality or fictionality of a text in some critical way, which is frequently done in postmodernist fiction. Non-critical metafiction does not criticize or undermine the artificiality or fictionality of a text and can, for example, be used to 'suggest that the story one is reading is authentic'.[13]

Generally media-centred/truth- or fiction-centred metafiction[edit]

While all metafiction somehow deals with the medial quality of fiction or narrative and is thus generally media-centred, in some cases there is an additional focus on the truthfulness or inventedness (fictionality) of a text, which merits mention as a specific form. The suggestion of a story being authentic (a device frequently used in realistic fiction) would be an example of (non-critical) truth-centred metafiction.

Examples[edit]

Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman[edit]

It is with LOVE as with CUCKOLDOM—

—But now I am talking of beginning a book, and have long had a thing upon my mind to be imparted to the reader, which if not imparted now, can never be imparted to him as long as I live (whereas the COMPARISON may be imparted to him any hour of the day)—I'll just mention it, and begin in good earnest.

The thing is this.

That of all the several ways of beginning a book which are now in practice throughout the known world, I am confident my own way of doing it is the best—I'm sure it is the most religious—for I begin with writing the first sentence—and trusting to Almighty God for the second.[14]

In this scene Tristram Shandy, the eponymous character and narrator of the novel, foregrounds the process of creating literature as he interrupts his previous thought and begins to talk about the beginnings of books. The scene evokes an explicitly metafictional response to the problem (and by addressing a problem of the novel one is just reading but also a general problem the excerpt is thus an example of both direct and indirect metafiction, which may additionally be classified as generally media-centred, non-critical metafiction). Through the lack of context to this sudden change of topic (writing a book is not a plot point, nor does this scene take place at the beginning of the novel, where such a scene might be more willingly accepted by the reader) the metafictional reflection is foregrounded. Additionally, the narrator addresses the reader directly, thereby confronting the reader with the fact that they are reading a constructed text.

David Lodge, The British Museum is Falling Down[edit]

Has it ever occurred to you that novelists are using up experience at a dangerous rate? No, I see it hasn't. Well, then, consider that before the novel emerged as the dominant literary form, narrative literature dealt only with the extraordinary or the allegorical – with kings and queens, giants and dragons, sublime virtue and diabolic evil. There was no risk of confusing that sort of thing with life, of course. But as soon as the novel got going, you might pick up a book at any time and read about an ordinary chap called Joe Smith doing just the sort of things you did yourself. Now, I know what you're going to say – you're going to say that the novelist still has to invent a lot. But that's just the point: there've been such a fantastic number of novels written in the past couple of centuries that they've just about exhausted the possibilities of life. So all of us, you see, are really enacting events that have already been written about in some novel or other.[15]

This scene from The British Museum is Falling Down (1965) features several instances of metafiction. First, the speaker, Adam Appleby (the protagonist of the novel) discusses the change the rise of the novel brought upon the literary landscape, specifically with regards to thematic changes that occurred. Second, he talks about the mimetic aspect of realist novels. Third, he alludes to the notion that the capabilities of literature have been exhausted, and thus to the idea of the death of the novel (all of this is explicit, critical indirect metafiction). Fourth, he covertly foregrounds that fact that the characters in the novel are fictional characters, rather than masking this aspect, as would be the case in non-metafictional writing. Therefore, this scene features metafictional elements with reference to the medium (the novel), the form of art (literature), a genre (realism), and arguably also lays bare the fictionality of the characters and thus of the novel itself (which could be classified as critical, direct, fiction-centred metafiction).

Jasper Fforde, The Eyre Affair[edit]

The Eyre Affair (2001) is set in an alternate history in which it is possible to enter the world of a work of literature through the use of a machine. In the novel, literary detective Thursday Next chases a criminal through the world of Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre. This paradoxical transgression of narrative boundaries is called metalepsis, an implicitly metafictional device when used in literature. Metalepsis has a high inherent potential to disrupt aesthetic illusion[16] and confronts the reader with the fictionality of the text. However, as metalepsis is used as a plot device that has been introduced as part of the world of The Eyre Affair it can, in this instance, have the opposite effect and is compatible with immersion. It can thus be seen as an example of metafiction that does not (necessarily) break aesthetic illusion.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Waugh, Patricia (1984). Metafiction – The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction. London, New York: Routledge. p. 2.

- ^Imhof, Rüdiger (1986). Contemporary Metafiction – A Poetological Study of Metafiction in English since 1939. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag. p. 9.

- ^Jensen, Mikkel (2016) 'Janus-Headed Postmodernism: The Opening Lines of Slaughterhouse-Five' in The Explicator, 74:1, 8-11.

- ^Gass, William H. (1970). Fiction and the Figures of Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 24–25.

- ^Gass, William H. (1970). Fiction and the Figures of Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 24–25.

- ^Waugh, Patricia (1984). Metafiction – The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction. London, New York: Routledge. p. 2.

- ^Scholes, Robert (1979). Fabulation and Metafiction. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 111–115.

- ^Wolf, Werner, ed. (2011). The Metareferential Turn in Contemporary Arts and Media: Forms, Functions, Attempts at Explanation. Studies in Intermediality 5. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- ^Waugh, Patricia (1984). Metafiction – The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction. London, New York: Routledge. p. 3.

- ^Waugh, Patricia (1984). Metafiction – The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction. London, New York: Routledge. p. 3.

- ^Scholes, Robert (1979). Fabulation and Metafiction. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. p. 124.

- ^Wolf, Werner (2009). 'Metareference across Media: The Concept, its Transmedial Potentials and Problems, Main Forms and Functions'. Metareference across Media: Theory and Case Studies. Studies in Intermediality 4, eds. Werner Wolf, Katharina Bantleon, and Jeff Thoss. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 37-38.

- ^Wolf, Werner (2009). 'Metareference across Media: The Concept, its Transmedial Potentials and Problems, Main Forms and Functions'. Metareference across Media: Theory and Case Studies. Studies in Intermediality 4, eds. Werner Wolf, Katharina Bantleon, and Jeff Thoss. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 43.

- ^Sterne, Laurence (1759-1767/2003). The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. London: Penguin. p. 490.

- ^Lodge, David (1965). The British Museum Is Falling Down. London: McGibbon & Kee. pp. 129–130.

- ^Malina, Debra (2002). Breaking the Frame: Metalepsis and the Construction of the Subject. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. pp. 2–3.

Further reading[edit]

- Gass, William H., Fiction and the Figures of Life, Alfred A. Knopf, 1970

- Heginbotham, Thomas 'The Art of Artifice: Barth, Barthelme and the metafictional tradition' (2009) PDF

- Hutcheon, Linda, Narcissistic Narrative. The Metafictional Paradox, Routledge 1984, ISBN0-415-06567-4

- Levinson, Julie, 'Adaptation, Metafiction, Self-Creation,' Genre: Forms of Discourse and Culture. Spring 2007, vol. 40: 1.

- Scholes, Robert, Fabulation and Metafiction, University of Illinois Press 1979.

- Waugh, Patricia, Metafiction – The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction, Routledge 1984.

- Werner Wolf, ed., in collaboration with Katharina Bantleon, and Jeff Thoss. Metareference across Media: Theory and Case Studies. Studies in Intermediality 4, Rodopi 2009.

- Werner Wolf, ed., in collaboration with Katharina Bantleon and Jeff Thoss. The Metareferential Turn in Contemporary Arts and Media: Forms, Functions, Attempts at Explanation. Studies in Intermediality 5, Rodopi 2011.

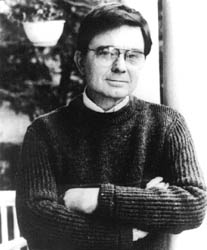

Coover in 2009 | |

| Born | February 4, 1932 (age 87) Charles City, Iowa, United States |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Writer |

| Alma mater | Southern Illinois University Carbondale Indiana University (B.A.) University of Chicago (M.A.) |

| Period | 1960s–present |

| Genre | Short story, novel |

| Spouse | María del Pilar Sans Mallafré (1959–present) |

| Children | |

Robert Lowell Coover (born February 4, 1932) is an American novelist, short story writer, and T.B. Stowell Professor Emeritus in Literary Arts at Brown University.[1] He is generally considered a writer of fabulation and metafiction.

- 4Bibliography

Life and works[edit]

Coover was born in Charles City, Iowa.[2] He attended Southern Illinois University Carbondale, received his B.A. in Slavic Studies from Indiana University in 1953,[3] then served in the United States Navy. He received an M.A. in General Studies in the Humanities from the University of Chicago in 1965. In 1968, he signed the 'Writers and Editors War Tax Protest' pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[4] Coover has served as a teacher or writer in residence at many universities. He taught at Brown University from 1981 to 2012.[5][6][7]

Coover's wife is the noted needlepoint artist Pilar Sans Coover.[8][9][10]They have three children, including Sara Caldwell.[11]

Coover's first novel was The Origin of the Brunists, in which the sole survivor of a mine disaster starts a religious cult. His second book, The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop., deals with the role of the creator. The eponymous Waugh, a shy, lonely accountant, creates a baseball game in which rolls of the dice determine every play, and dreams up players to attach those results to.

Coover's best-known work, The Public Burning, deals with the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in terms that have been called magic realism. Half of the book is devoted to the mythic hero Uncle Sam of tall tales, dealing with the equally fantastic Phantom, who represents international Communism. The alternate chapters portray the efforts of Richard Nixon to find what is really going on amidst the welter of narratives.

A later novella, Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears offers an alternate Nixon, one who is devoted to football and sex with the same doggedness with which he pursued political success in this reality. The theme anthology A Night at the Movies includes the story 'You Must Remember This', a piece about Casablanca that features an explicit description of what Rick and Ilsa did when the camera wasn't on them. Pinocchio in Venice returns to mythical themes.

Coover is one of the founders of the Electronic Literature Organization. In 1987 he was the winner of the Rea Award for the Short Story.

Awards and honors[edit]

- 1967 William Faulkner Foundation Award for notable first novel for The Origin of the Brunists

- 1987 Rea Award for the Short Story

William Faulkner, Brandeis University, American Academy of Arts and Letters, National Endowment of the Arts, Rea Lifetime Short Story, Rhode Island Governor's Arts, Pell, and Clifton Fadiman Awards, Rockefeller, Guggenheim, Lannan Foundation, and DAAD fellowships[12]

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

Novels[edit]

- The Origin of the Brunists. 1966.

- The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop. (1968)

- The Public Burning (1977)

- Gerald's Party (1986)

- Pinocchio in Venice (1991)

- John's Wife (1996)

- Ghost Town (1998)

- The Adventures of Lucky Pierre: Director's Cut (2002)

- Noir (2010)

- The Brunist Day of Wrath (2014)

- Huck Out West (2017)

- The Baby Sitter

Short fiction[edit]

Collections

- Pricksongs & Descants (1969) (collection)

Stories[13]

| Title | Year | First published | Reprinted/collected | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The crabapple tree | 2015 | 'The crabapple tree'. The New Yorker. 90 (43): 58–61. January 12, 2015. |

- 'The Babysitter,' inspiration for The Babysitter (1969) (short story)

- A Political Fable (1968, 1980, 2017) (novella)

- Originally published as a short story 'The Cat in the Hat for President' in New American Review, 1968; re-released under its original title in 2017.

- Spanking the Maid (1982) (novella)

- In Bed One Night & Other Brief Encounters (1983) (collection)

- Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears (1987) (novella)

- A Night at the Movies or, You Must Remember This (1987) (themed anthology)

- Dr. Chen's Amazing Adventure (1991) (novella)

- Briar Rose (1996) (novella)

- The Grand Hotels (of Joseph Cornell) (2002) (novella)

- Stepmother (2004) (novella)

- A Child Again (2005) (collection)

- 'The Case of the Severed Hand'. Harper's Magazine. 317 (1898): 74–80. July 2008.

- Reprinted in Noir.

- 'White-bread Jesus'. Harper's Magazine. 317 (1903): 79–88. December 2008.

- Reprinted in The Brunist Day of Wrath, Chapter I.2

- 'An Encounter'. Fortnightly Review. October 2010.

- 'The Old Man'. Fortnightly Review. February 2011.

- 'Going for a beer'. The New Yorker. March 14, 2011.

- 'Matinée'. The New Yorker. July 25, 2011.

- 'The Goldilocks Variations'. The American Reader. Vol. 1 no. 7. August 2013.

- 'The Colonel's Daughter'. The New Yorker. September 2, 2013.

- 'The Frog Prince'. The New Yorker. January 27, 2014.

- 'The Waitress'. The New Yorker. May 19, 2014.

- 'The Crabapple Tree'. The New Yorker. January 12, 2015.

- 'The Hanging of the Schoolmarm'. The New Yorker. November 28, 2016.

- The Cat in the Hat for President. See A Political Fable (April 2017)[14] (novella)

- Going for a Beer. Selected Short Fictions (February 2018)[15] (collection)

- 'The Enchanted Prince'. The Evergreen Review (October 2018).

Robert Coover New Yorker

Plays[edit]

- A Theological Position (1972) (plays)

Robert Coover The Babysitter

Non-fiction[edit]

- 'The End of Books'. The New York Times. June 21, 1992. (essay)

References[edit]

- ^'Literary Arts'. Brown University.

- ^Evenson, Brian (2003). Understanding Robert Coover. University of South Carolina Press. p. 1. ISBN978-1570034824.

- ^Stengel, Wayne B. (2001). 'Robert Coover'. In Fallon, Erin; Feddersen, R.C.; Kurtzleben, James; Lee, Maurice A.; Rochette-Crawley, Susan (eds.). A Reader's Companion to the Short Story in English. Routledge. pp. 118–32. ISBN1-57958-353-9.

- ^'Writers and Editors War Tax Protest' January 30, 1968, New York Post

- ^'Unspeakable Practices V: Celebrating the Life and Work of Robert Coover'. The Providence Phoenix. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07.

- ^'Unspeakable Practices V: Festival Bios'. Brown University.

- ^'Unspeakable Practices V: Celebrating Robert Coover'. Brown University.

- ^Born María del Pilar Sans Mallafré

- ^'Pilar Sans Coover'.

- ^'Contemporary Midwest Writers Series, Nos. 1,2 Author(s): Franklyn Alexander, Robert Bly, Robert Coover and Camille Blachowicz'. The Great Lakes Review. 3 (1): 66–73. Summer 1976. JSTOR41337445.

- ^Current Biography Yearbook 1991, volume 52. H. W. Wilson. 1992. p. 159.

- ^https://www.brown.edu/academics/literary-arts/faculty/robert-coover/robert-coover

- ^Short stories unless otherwise noted.

- ^https://www.orbooks.com/catalog/cat-hat-president-robert-coover/

- ^http://books.wwnorton.com/books/detail.aspx?ID=4294994511

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Coover. |

- 'Robert Coover'. Providencephoenix.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2011-08-19.– Interview

- Robert Coover on IMDb

- Rettberg, Scott. 'A History of the Future of Narrative: Robert Coover on Vimeo'. Vimeo.com. Retrieved 2011-08-19.– Novelist Robert Coover's keynote address at the Electronic Literature in Europe seminar (elitineurope.net), September 13, 2008. Introduced by Scott Rettberg. Videography by Martin Arvebro.

- Lydon, Christopher (2008-12-09). 'In the Obama Moment: Robert Coover'. Radio Open Source. Radio Interview

- Bookworm Interviews (Audio) with Michael Silverblatt: December 2005, December 2005